When Freud Was Asked To Name "Ten Good Books" - He Simply Couldn't Resist Interpreting The Question.

He saw things no one else did and asked questions no one else would. This little known anecdote illuminates the brilliance of a man who approached everything in his own unique Freudian way.

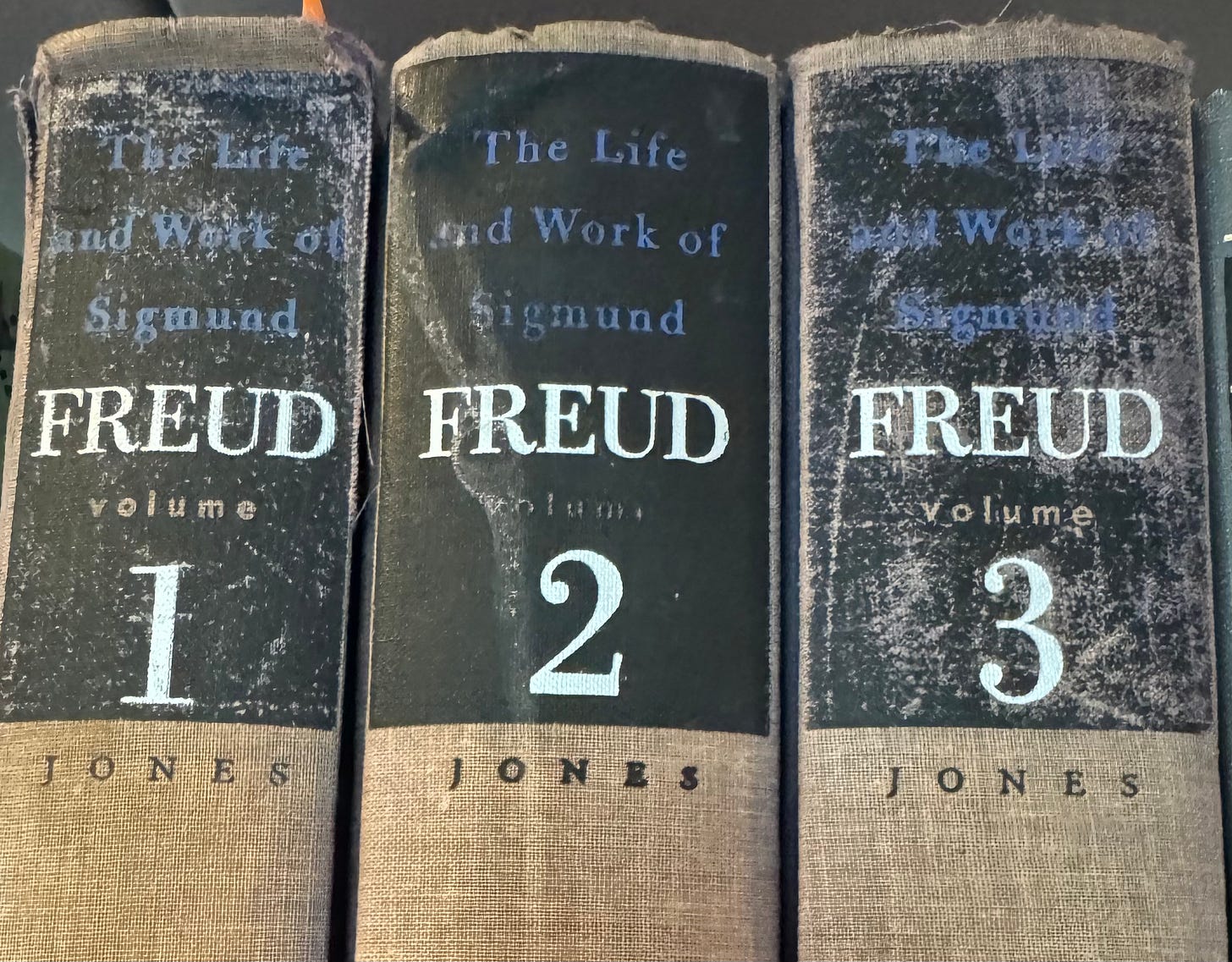

I’ve been reading Ernest Jones’ three volume biography of Freud - which is actually a lot more interesting that you might first suppose. It’s full of wonderful personal anecdotes which personalise the man everybody in the 21st century thinks they know about but don’t. Whatever issues you have with Freud’s theories, in reading him you simply have to respect his mind. He asks questions that no one else asks, and pursues avenues no one even thought to look.

In Volume Three Jones shares one of these stories which really illustrates the way Freud thinks. In 1907 Viennese publisher Hugo Heller invited a handful of Europe’s intelligentsia to submit a choice of “ten good books.” I’m sure many of those invited like Arthur Schnitzler and August Forel did as they were told. Freud, on the other hand, had to interrogate the question itself. It’s worthy of reproducing in its entirety here, since very few of you are likely to pick up the three volume set.

In Freud’s Words:

"You ask me to name "ten good books' without vouchsafing any explanation, and so leave it to me not only to select the books but also to interpret the request.

Accustomed as I am to heed minute signs I must adhere to the wording in which you couch your enigmatic request. You did not say the ten most magnificent works of world literature' - to which I should have had to reply, as would so many others, Homer, the tragedies of Sophocles, Goethe’s Faust, Shakespeare's Hamlet, Macbeth and so on.

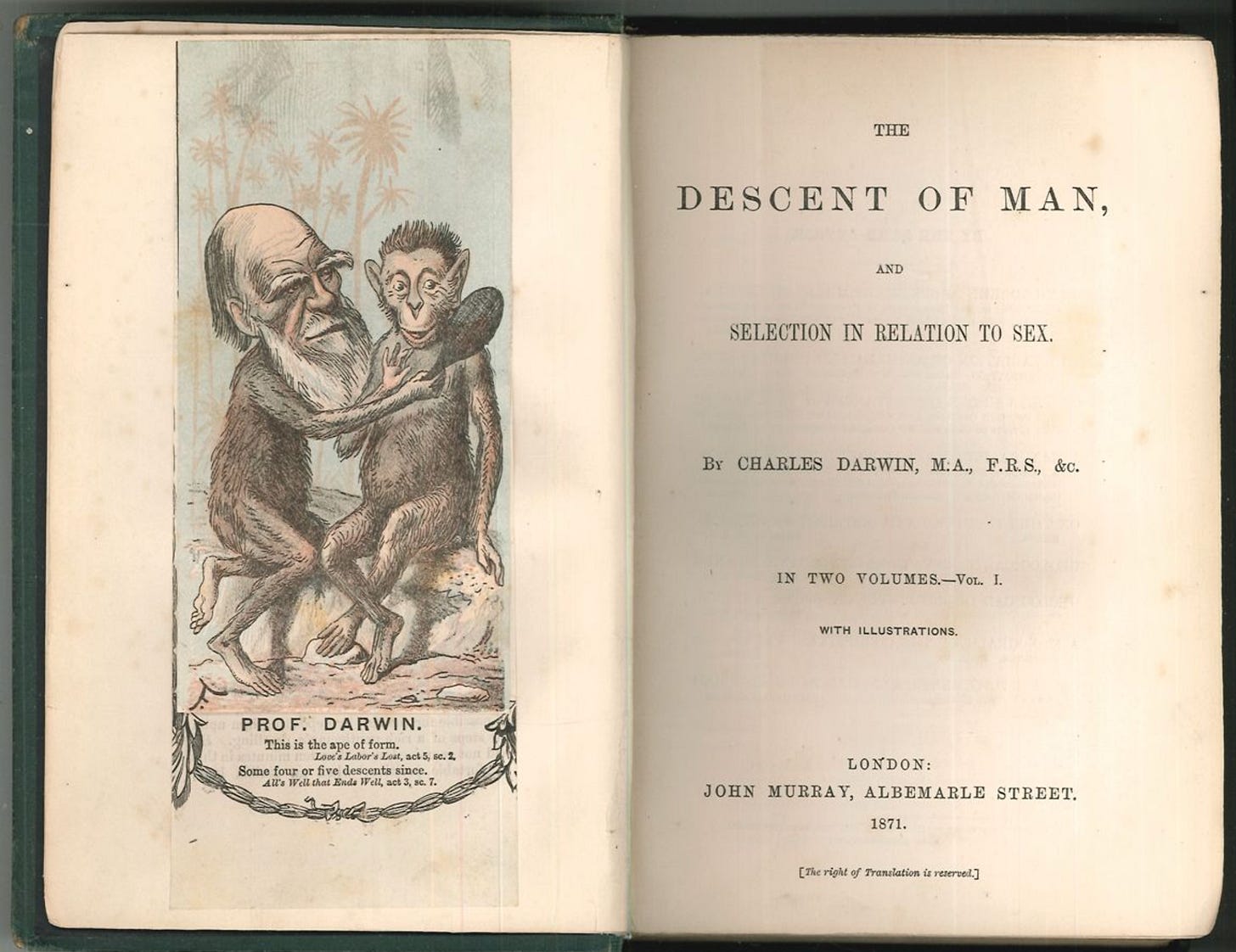

"Neither did you say the 'ten most important' books, which would have necessitated including such scientific achievements as those of Copernicus, the book on belief in witches by the old physician Johann Weier, Darwin's Descent of Man, and others.

Nor did you even ask for my 'favourite books’, among which I should not have forgotten Milton's Paradise Lost and Heine's Lazarus. I think therefore that special significance attaches to your word 'good,' and that it carries the same implication as when we speak of 'good' friends, books to which a man owes some of his knowledge of life and his Weltanschauung; books which one has enjoyed and gladly recommends to others, but which do not evoke awe or dwarf one by their great stature.

"I shall name for you ten such 'good' books as they occur to me without much reflecting.

Multatuli, Briefe und Werke

Kipling, Jungle Book

Anatole France, Sur la pierre blanche

Zola, Fécondité

Merekowsky, Leonardo da Vinci

Gottfried Keller, Leute von Seldwyla

Conrad Ferdinand Meyer, Huttens letzte Tage

Macaulay, Essays

Gomperz, Griechische Denker

Mark Twain, Sketches

"I do not know what you intend to do with this list. It seems very odd to me, and I cannot quite leave it without comment.”

At this point Freud goes into some detail about some of his choices, but I’ve decided to redact that. He closes with a similar kind of apology:

“Your request to name ten good books touches on something about which immeasurably much might be said. And so I conclude in order not to become more loquacious.”

Many of his choices may not be your cup of tea (or, like me, there are some you’ve never even heard of), I hope this little window into his mind will have made you like him a little more. I certainly did.

—

The above is directly quoted from The Life and Work of Sigmund Frued, Volume III, by Ernest Jones (1957) pages 422-423.