The Hidden Mystical Life of Carl Jung:

From seances, dreams and the occult, to Eastern wisdom's place in Western psychology.

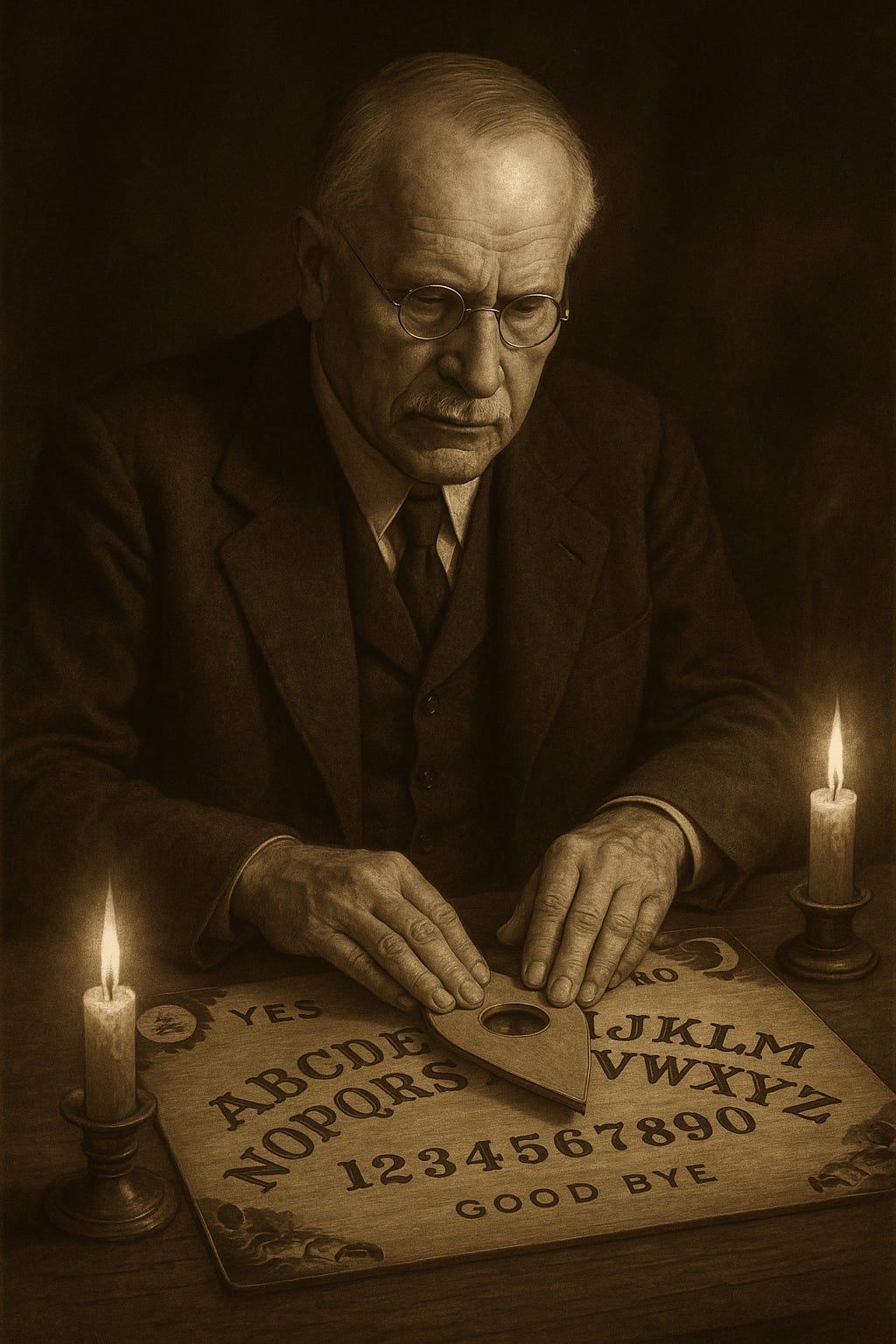

Next time you pick up a Ouija board - spare a thought for Carl Jung. He may not have used one himself, however he was no stranger to a séance. In his younger years he could have been found around a round wooden table, illuminated by flickering candles, seeking to communicate with the dead. He even wrote his PhD thesis on this material, “On the Psychology and Pathology of So-Called Occult Phenomena,” which was based on the seances held by a psychic medium, Jung’s own cousin! She later discovered to have been faking it. In later life his interest shifted to the East - particularly the I-Ching.

There were a lot of reasons that led to the split between Freud in Jung in 1913 and chief among them, for Freud anyway, was Jung’s continued obsession with all things mystical — an interest Freud feared would deny the new science of psychoanalysis the legitimacy he craved for it.

Jung didn’t try to keep his extra-curricular interests in the paranormal from Freud. During their famous first conversation, purported to have lasted a full thirteen hours, a mysterious and sudden bang was heard emanating from Freud’s bookshelf. As Jung notes in his autobiography:

“ . . . we both started up in alarm. I said to Freud: ‘there, that is an example of a so-called catalytic exteriorisation phenomenon [telekinesis]’

‘Oh come,’ he exclaimed. ‘That is sheer bosh.”

‘It is not,” I replied. “You are mistaken, Herr Professor. And to prove my point I now predict that in a moment there will be another loud report!’

Sure enough, no sooner had I said the words than the same detonation went off in the bookcase..

Freud only stared aghast at me. I do not know what was in his mind, or what his look meant. In any case, this incident arounds his mistrust of me, and I had the feeling that I had done something against him.”

— (MDR*, 179)

The seed of this mistrust would grow well beyond the split between Jung and Freud and would come to define the difference between Freudian and Jungian traditions that still exists to this very day. Sadly, both schools are far too often reduced to caricatures of themselves, with Jungians portrayed as being wildly woolly New-Agers and Freudians as dogmatically obsessed with sex. Neither of these summations are true.

Jung after Freud: The confrontation with the unconscious

In his early years Jung contributed a great deal to conventional psychology and psychiatry. He helped develop and perfect the word association test, contributed to the emergence of schizophrenia as a diagnostic condition, created the theory of psychological types and advanced the theory of complexes. But it is indeed after his break with Freud that things get interesting. The trauma of that break sent Jung into a mental breakdown that he later came to understand as a “confrontation with my unconscious” — an event that broke Jung wide open to concepts well beyond the confines of conventional psychology. He wrote in his autobiography:

“The years when I was pursuing my inner images were the most important of my life — in them everything essential was decided. It all began then; the later details are only supplements and clarifications of the material that burst forth from the unconscious and that first swamped me. It was the prima material for a lifetime’s work.” — (MDR, 225).

This productive period produced ideas like the collective unconscious and the archetypes. These concepts enabled Jung to push well beyond the limits of the personal unconscious, the domain of classical psychoanalysis, and develop his own unique path called Analytical Psychology though still better known simply as Jungian Psychology. What people are less familiar with is how Jung’s curiosity took him around the world, through reading and travel, with the aim of uncovering and incorporating wisdom missed or ignored by the West. Jung went to North and East Africa, the Taos Pueblo in New Mexico, and traveled extensively in India (where he almost met the famed guru Ramana Maharshi). In each location he met with local people to try and understand their beliefs and symbols.

Check out my recent article A new personality type - ‘Otrovert’ - is here to make life even more confusing in GQ Magazine about how Jung’s concepts of personality types like introversion and extraversion are often misused today.

While Jung’s approach no doubt conveys the superior Eurocentric tone of his time — his open mindedness to non-Western ideas and their application to human psychology was unusual. Jung was keen to seek what was universal about the human psyche and searched around the world to find common symbols in various ritual practices, religions, rituals, narratives, and myths. At the same time, he was wary of what we would today understand as cultural appropriation — warning that ideas from elsewhere cannot be wholesale applied to Western experience. Though his interest was in the universal, he acknowledged the importance of local, trans-generational histories, and that cultural symbols and narratives are deeply contextual.

Not finding his answers in Western Psychology, Jung looks East:

Around the time that Jung was developing his own post-Freudian path, texts and ideas from the East became more available in the West through newly translated ancient texts. It was clear to Jung early on that these texts were potential treasure troves that resonated with his own thought. It might surprise you to learn that he not only engaged personally with these texts, but that he wrote commentaries in the early German translations of the I-Ching and the Secret of the Golden Flower — later translated in to English as well.

The I-Ching:

In his forward to the I-Ching, Jung notes that it is “important to cast off the prejudices of the Western mind” (xxii) by relinquishing a purely scientific point of view and taking another approach. While this is exactly the kind of open-mindedness that freaked out Freud, Jung still wasn’t altogether comfortable embracing what was likely to be perceived by his peers as kooky foreign mysticism. In the introduction to the I-Ching he admits:

“I had not been feeling too happy in the course of writing this foreword, for, as a person with a sense of responsibility towards science, I am not in the habit of asserting something I cannot prove or at least present as acceptable to reason . . . I have undertaken it because I myself think that there is more to the ancient Chinese way of thinking than meets the eye” (I-Ching, xxxiii).

Whether this is a rhetorical device or not, we cannot be sure. His work around concepts like synchronicity and alchemy were already rather unscientific and mostly dismissed by the establishment. So in many ways, reaching out towards the wildly unconventional falls pretty firmly in Jung’s wheelhouse. Jung was also already comfortable operating in undiscovered terrain. In the developing field of psychotherapy, Jung notes:

“we become more accustomed to adopting methods that work even though for a long time we may not know why … In the exploration of the unconscious we come upon very strange things, from which a rationalist turns away with horror, claiming afterwards that he did not see anything. The irrational fullness of life has taught me never to discard anything, even when it goes against all our theories or otherwise admits of no immediate explanation” (I-Ching, xxxiv).

In this quote, we see Jung sounding very much like Freud, though the “strange things” each is referring to is quite different.

Jung notes that engagement with the I-Ching is reliant upon a commitment to self-knowledge, and that the divination tool is wasted without it. In this sense self-knowledge goes deeper than the usual one associated with classical psychoanalysis, because it’s really knowledge that goes beyond the self alone and into the realms of something larger and more universal — realms covered in the philosophies of Taoism, Buddhism, and Advaita Vedanta more so than Western psychology. Jung’s ideas around archetypes and the collective unconscious may be very different from these Eastern concepts — but they afforded him an opportunity to deepen and develop his fledgling ideas on the one hand, and frame them for Westerners on the other.

The Secret of the Golden Flower:

Even more inscrutable than the I-Ching is The Secret of the Golden Flower, an ancient Taoist text otherwise known as the Chinese Book of Life. Jung wrote a commentary to it when it was first translated into German by Richard Wilhelm. The Golden Flower ignited Jung’s own interest around personal transformation, a concept that he was exploring in his study of alchemy and the development of his theory of individuation. Jung finds the Chinese Taoist perspective quite mind-blowing, yet renews his warning to enthusiastic Westerners not to mistakenly throw off their Western worldview too quickly and find themselves “pitiably imitating” the East rather than truly integrating its wisdom.

Jung goes on to explain that he developed Analytical Psychology in complete ignorance of the Chinese philosophy contained in these texts. However, he has come to understand that unconsciously at least, he had all along been moving in that direction the whole time. Jung relates this to his development of the idea of the collective unconscious.

“A higher and wider consciousness which only comes by means of assimilating the unfamiliar, tends toward autonomy, toward revolution against the old gods who are nothing other than those powerful, unconscious, primordial images which, up to this time, have held consciousness in thrall.” (Secret of the Golden Flower, 84).

Through the lens of modern psychology, Jung continues his commentary by describing concepts from the text that, though familiar to many readers today, would have been quite alien to Western readers in the 1930s. Among these are “Tao” or “the way”, “chi” energy, and the concept of “oneness” or “unity” which is represented in the golden flower, which Jung relates to his own work with mandalas. To this he integrates elements from Western philosophy and spirituality: concepts like logos, eros, and Western conceptualisations of the soul, alongside his own concepts of the collective unconscious, archetypes, and the contrary forces of anima and animus.

All of this conceptual integration is gathered towards the therapeutic goal to free the individual from the domination of the unconscious. Just as it was for Freud, this liberation is accomplished through increased self-knowledge that is gained in the analytic process. Unlike Freud, however, Jung understands the nature of the unconscious very differently.

When Freud coined that now famous maxim, “Where id was, ego shall be,” he was referring specifically to the personal unconscious or “the repressed” which should be brought into consciousness. Jung does not dismiss personal unconscious, rather, he incorporates it into the much larger concept of collective unconsciousness — an aspect of the unconscious, populated by universal archetypes, shared with the whole of human kind, alive and dead.

While ideas from Eastern Spirituality, Philosophy, and Mysticism do not map directly onto Jung’s ideas, they do resonate more closely with them than many concepts from Western Psychology. This is most notable in Jung’s conception of the numinous, the archetypes, and synchronicity, all of which elude “scientific” understanding.

Jung’s unique integration of Eastern philosophy and Western psychology is no easy fit:

The aim of Jung’s commentaries are to build a bridge between the paradigms of Western Psychology and Eastern Philosophy. While that bridge is a surely a clunky one, we must remember that in his time, Jung was a cutting-edge pioneer at this meeting of worldviews. He repeatedly states that one paradigm should not be dispensed of for another, but rather integrated into a whole. As complementarity is so central to his work, he argues for it here too: like yin and yang, the philosophies developed by East and West are missing important insights that can be gained from one another — a great opportunity for synthesis.

Importantly, Jung points to the universally shared experience of suffering — an experience that drives people to both psychotherapy and spiritual guidance (famously one of the four noble truths of Buddhism). Jung notes that it’s suffering that drives all cultures to seek something beyond themselves:

“it is the tremendous experiment of becoming conscious, which nature has imposed on mankind, uniting the most diverse cultures in a common task [to overcome suffering]” — (Golden Flower, 136).

Freud was a master at creating a thoroughly Western paradigm through which to comprehend the personal unconscious — a paradigm that in its admittedly flawed nature focuses on analysis: an over-emphasis on thinking. What initially attracted Jung to Freud, however, was sheer scope and creativity of his seminal work The Interpretation of Dreams, a book which illuminated the deeply symbolic creativity of the unconscious mind.

Jung’s journey from Freud’s paradigm of the personal unconscious toward developing his own theory of the collective unconscious began through the doors that were open to him at the time — Christian theology, Greek and Roman mythology, and medieval alchemy. The arrival of newly translated texts from the East created a whole new opportunity that human experience in a novel way for Western eyes.

While there’s a long distance between Jung’s interest in the seances of his early years and Eastern Philosophy later, what unites them is his capacity to withhold critical judgement and embrace the unknown and lesser understood. Whereas Freud shed a brilliant light on the lesser-known parts of our personal psyches, Jung went beyond that to inquire about the transpersonal and collective. His seeking was always there but was re-ignited by his confrontation with the unconscious, an event, possibly psychotic, that he submitted himself to fully to better understand himself and the human psyche at large. In his courage to pursue this, and write about it, he opened up an even wider door to what lies beyond the known in all of us.

So what are your thoughts? Should Western psychology be open to insights from the East, or should it keep to its own lane? Please let me know in the comments. If you enjoy exploring the hidden histories of psychology, subscribe to Applied Psychodynamics for new posts every week.

This is a fully revised and updated version of an Medium article that has now been deleted.

Aaron Balick, PhD, is a psychotherapist, author, and GQ psyche writer exploring the crossroads of depth psychology, culture, and technology.

Great post Aaron, thank you. As I read this, I am sitting with the alchemical symbology (not literal metallurgy) as the core link between the eastern metaphysic and western psychological traditions. It helps us to understand psychological growth (Jung's individuation process) as a archetypal imprint for healing which exists in consciousness itself. Think about flesh rejecting a splinter, so to do anxiety and depression help us see where the true self is trying to push an unwelcome influence out. Anyway, that is just what was in my mind, Peter Kingsley's Catafalque also came to mind for further on these mystic thoughts from a contemporary world view. Thanks again for sharing!