AI and Mental Health, Part Two: AI Companions or Dangerous Liaisons?

In the midst of a loneliness epidemic, young people are seeking AI companionship more than ever. How worried should we be?

Should you have the bad luck of finding yourself addicted to heroin and wanting to get off it, you’ll probably agree that methadone is a pretty good option. Few people, however, would choose methadone as a preventative to becoming addicted to heroin. But is that what’s happening in the growing claims that AI companions may be a solution to the loneliness epidemic?

Is something really better than nothing?

This may be a faulty metaphor, but I think it resonates. To carry it forward, there’s a lot of competition at the moment for the opiate of the masses: religion, distraction, and now AI companionship. Nobody wants our young people to suffer - and everybody wants a bit of good news, which is why headlines like AI Companions Reduce Loneliness are often welcome; but how welcomely do we receive the headline Methadone Reduces Heroin Dependence?

The findings from the report that instigated these headlines are hardly surprising:

The reduction of loneliness is better than doing nothing or watching YouTube videos, and on par to that as talking to a real human.

“Feeling heard” is the biggest driver of feeling less lonely.

AI chatbots designed for companionship work better than generalised AI bots.

The researchers conclude by suggesting that positive design implications include building “LLM-based chatbots with empathic features designed to make consumers feel heard.” Funny, that, this use of the word “consumers” when we are talking about people. Is it just me or does developing chatbots that better perform empathy to enable users to “feel heard” by a bots that don’t hear or feel empathy feel a little Black Mirror? Indeed talking to something may feel better than nothing, but what are the long term consequences of the something that’s on offer?

This is the second newsletter in the Substack series AI and Mental Health. Check out Part One: What We Know, What We Fear - and be sure to subscribe to receive future editions.

As I’ve written elsewhere, I do not dispute the fact that the feelings that people have for their AI companions are real, nor do I disparage those feelings. I do, however, have serious concerns about a culture in which AI’s performance of of a caring companion may be becoming the primary way in which people’s relational needs are met.

New Study: 72% of US teens have used AI companions

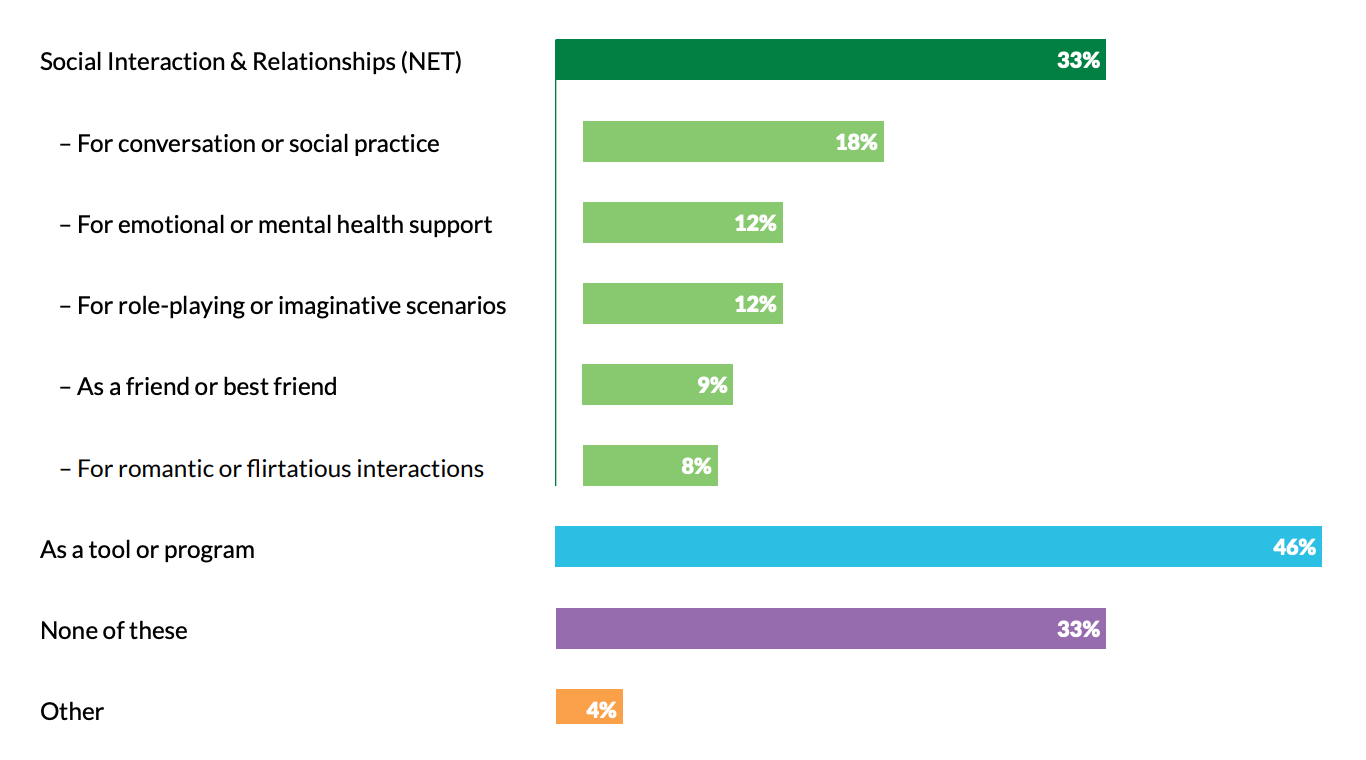

Earlier this summer Common Sense Media released a report noting that nearly three out of four US teens have tried an AI companion at least once, and just over half are regular users (13% chatting daily and 21% a few times a week), proving that engaging with these bots is hardly a niche activity. Importantly, more than a third of users are doing so explicitly for social interaction and relationships. In answer to the question “How do you use or view AI companions?” Common Sense Media’s report found:

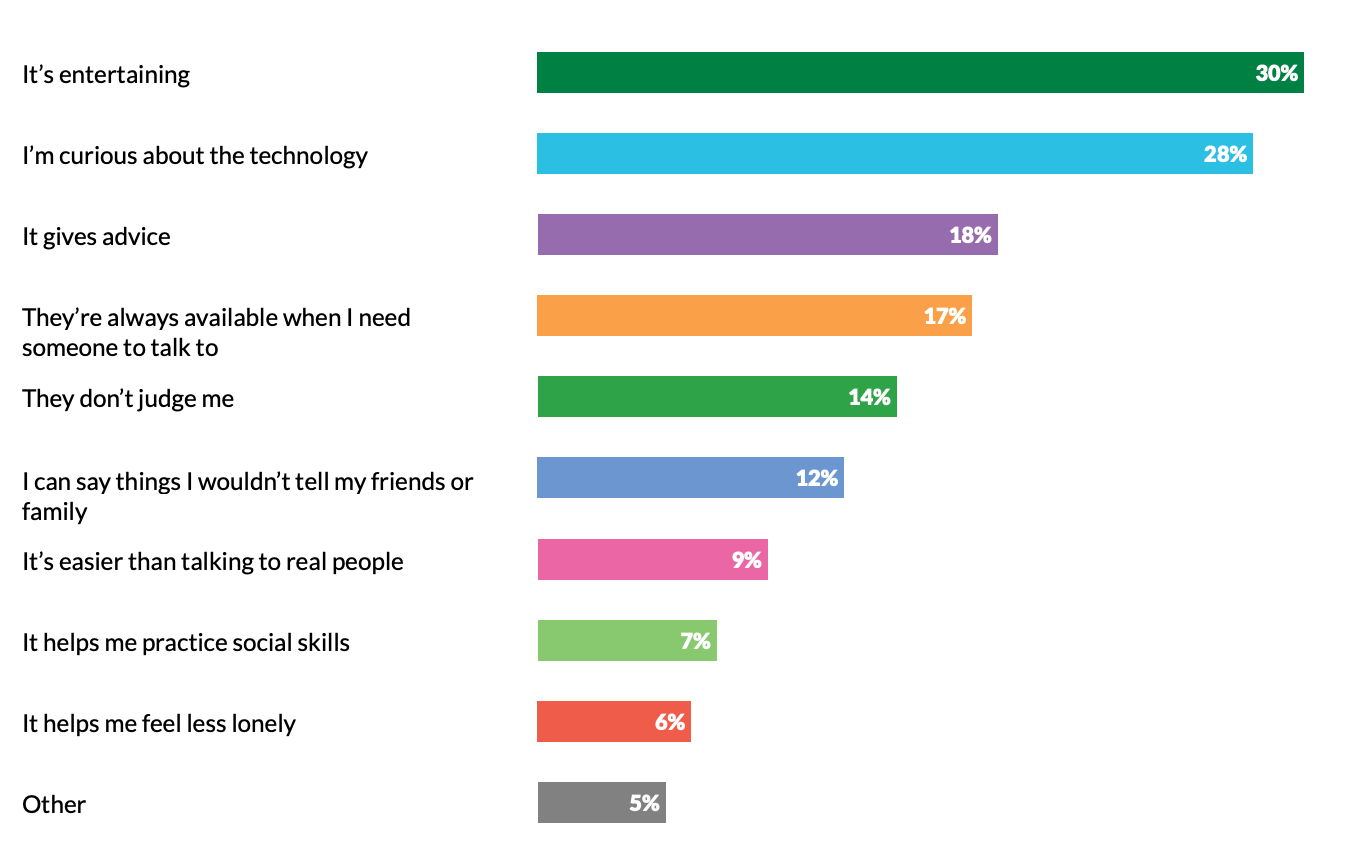

When asked “Why do you use AI companions” the highest answers were that “It’s entertaining” (30%) and “I’m curious about technology” (28%). However, a substantial number of respondents use it for considerably more important reasons including receiving advice, being available to talk when they need it, non-judgement, finding it easier than talking to real people, and helping them feel less lonely:

These findings are likely to be quite worrying to parents and others who are witnessing young people’s emotionally sensitive inner lives being outsourced to emotionless AI companions that are run by giant corporations with little accountability.

Nearly 70% of respondents find conversations with real-life friends more satisfying, but that still leaves nearly a third feeling the reverse. We might credibly assume that this third is made up of more vulnerable young people who find those connections with real others hard to create and maintain.

The same is true for how trustworthy young people find their AI companions; while 77% don’t trust or somewhat trust information gleaned from AIs, that still leaves nearly a quarter who trust AI quite a bit or completely - this number skews higher for younger teens. Could we make the same assumption that more vulnerable young people are more likely to trust it more? I think so.

We can be somewhat reassured that 80% of teens who used AI companions still spent more time with real friends than with their chatbots - but will this trend continue? Further, how worried should we be about the 6% for whom the reverse is true? Like so many things of this nature, it’s the people that are already vulnerable that are at the most risk.

Regulation, accountability and oversight

I hope we’ve learned from social media that we cannot depend on the corporations creating these products (and that’s what they are, products) to police themselves. We are also currently living in a de-regulatory period where government oversight is negligible, particularly in the USA where many of these companies are based. Still, there were a few new stories last week that at least gives us a glimmer of hope.

California’s AI Regulation Bill: In one of the first major steps to address the dangers of AI companionship California’s legislature has passed a “first of its kind” AI regulation bill. The Algorithm reports that California’s bill would require “AI companies to include reminders for users they know to be minors that responses are AI generated. Companies would also need to have a protocol for addressing suicide and self-harm and provide annual reports on instances of suicidal ideation in users’ conversations with their chatbots.”

Federal Trade Commission Inquiry: The FCC has launched an inquiry into seven companies including Google, Meta, OpenAI, Snap, and X that seeks to better understand the impact and revenue model of chatbots.

The read on these moves by The Algorithm (published by MIT Tech Review) is that these events and others are putting pressure on AI companies and that they are paying attention. However, identifying the problems is a lot harder than finding solutions. “As it stands,” writes James O’Donnell in The Algorithm, “ it looks likely we’ll end up with exactly the patchwork of state and local regulations that OpenAI (and plenty of others) have lobbied against … Companies have built chatbots to act like caring humans, but they’ve postponed developing the standards and accountability we demand of real caregivers. The clock is now running out.”

AI is filling a void that needs to be addressed by people

While we lobby for further regulation and fight to hold companies accountable, we need to be asking ourselves as a society some very serious questions about the void that AI companions seek to fill. Are we not providing good enough access to spaces where young people can speak without being judged? To be available when they really need to talk? To help them feel less lonely by giving them the skills they need to meet complex interpersonal challenges?

These are complex questions that need to be asked at every level, in the home, at school, and as a matter of public policy. That is undoubtedly a steep hill to climb, but it’s not insurmountable. After all the psychology that we need to address here hasn’t changed at all.

Young people today need to be taken seriously, listened to, and heard, just as they always have. The only thing that has changed is the ubiquity of access to alternatives, and the sophistication of those alternatives.

It comes down to each of us in whatever role we have to play in relation to the younger generation not only to limit and supervise access to potentially damaging tech, but to actively create spaces where young people can actually be heard and in which their loneliness can actively be met. We need to give them the tools to do this by way of our relationships with them. One place to start would be to overcome our own addiction to distraction. After all, if we’re all on methadone how we can expect the next generation to come off it?

If these themes matter to you, subscribe and join me in this unfolding series. Share your own encounters with AI and therapy—formal or informal. Comment, question, challenge. Together we can untangle what’s hype, what’s harm, and what might actually help.

Don’t miss the upcoming conference on the intersection of AI and psychotherapy hosted by the United Kingdom Council for Psychotherapy, Friday, November 28th at 10:00am.

Aaron Balick, PhD, is a psychotherapist, author, and GQ psyche writer exploring the crossroads of depth psychology, culture, and technology.

I always take a lot of interest in this type of article. Because of my experience with both AI and human therapy.

In the UK, counselling and therapy is an unregulated industry. That’s important to note because I don’t think the training is enough, or the requirements for “membership”.

I’ve had 10 years experience as a client.

When I weigh up the pros and cons of AI vs human - having used ChatGPT for over a year now.

It’s a lot closer as a contest than I imagined it would be.

And the LLM wins. For me.

Anecdotal.

Maybe not useful.

Both have dangers for vulnerable people.

One costs a lot of money, unless it’s “evidenced based” and short term on the NHS.

The requirement for a solution to the current societal issue of poor mental health - shouldn’t lie with computers. But in the absence of most governments inability to improve provision, we can’t scale humans up quick enough.

I think we should work out how to make it work with the least amount of harm caused.